Thanks to all of you who have followed us on this site. We are moving but please come with us! Henceforth this blog will continue on Senate House Library’s website at http://www.senatehouselibrary.ac.uk/category/historic-collections/. We hope you’ll continue to follow us there.

Senate House Library Treasures Volume: Looking Back

Commissioning articles for a treasures volume is an uneven experience. Some people accept an invitation immediately, while other books are hawked around for up to five times or so before a scholar agrees to write about them. A few people responded to the invitation with the query: “Why don’t you write this piece yourself?”, and sometimes, as emails flew to and fro and I wielded the editorial red pencil, I did wonder whether it would have been simpler to have been a single author than an editor. But the quality of the finished product would have suffered. As it was, a stellar team of contributors demonstrated the fact of institutional goodwill, as sixty busy people, not all of whom were connected with the University, took time to research and write 400-word entries. Not only that, but contributors came with new angles and with expertise in their areas. Myths which had lasted half a century or longer were debunked and new discoveries made. Some were disappointing: a unique incunable is more prestigious than one of two copies (item no. 5; but at least Senate House Library continues to have the only known complete copy in the world. The second copy, long in the Sorbonne, had initially been incorrectly identified). Others were exciting, adding nuggets of research to a coffee-table volume: for example, Brian Alderson, editor and translator of many children’s books, identified the anonymous illustrator of a scarce Victorian children’s book, Halt!

Producing the treasures volume was exhilarating and worthwhile. Editress Karen Attar has now published a short article in SCONUL Focus, 58 about the benefits of producing such a volume, “Making Treasures Pay? Benefits of the Library Treasures Volume Considered”, accessible here.

From the Reading Room: Byrom Research

I first visited the Reading Room longer ago than I care to admit when I started research for a PhD dissertation, which focused on the ‘Universal English Short-hand’ invented by John Byrom (1692-1763) diarist, poet, local political activist, linguist and FRS – all in all, something of a polymath. Now that I’m preparing an edition and biography of Byrom, as well as continuing my research into eighteenth-century shorthand more generally, I’ve returned to explore more of Carlton’s great collection. I’m really enjoying doing so : it’s a neglected but very rich mine with much to interest current and future researchers in a gamut of fields connected with the history of communications, education and palaeography. Byrom’s was a leading and influential early eighteenth-century shorthand, which he spent so much of his life teaching (for a princely five guinea sum) while also raising subscription support for a printed manual, published posthumously in 1767. Carlton’s collection contains extremely rare, at points unique, evidence relating to Byrom’s subscription project. As is clear from correspondence that Carlton preserved, Byrom’s manual came to be highly prized by shorthand collectors in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. So Carlton must have been all the more delighted with his own acquisition of what is a splendid association copy (CSC Byrom [1767] Box 3): this had been presented to Ralph Leycester, Squire of Toft (1699-1776), a leading proponent of Byrom’s system and a close friend for over four decades, whose own shorthand diaries I have been transcribing.

Another Byrom-related treasure in the collection is a letter written by him to Fisher Littleton (MS Carlton 35/12(i)), a Fellow Commoner of Emmanuel College Cambridge, fascinating as an instance of eighteenth-century ‘teaching-by-post’ and for showing that Byrom’s shorthand continued to be promulgated at Cambridge well after Byrom started teaching it in person there.

Senate House Library treasures volume: featuring the young George Grote

Thus Grote’s representation in the treasures volume was partly a celebration of corporate identity. Representation emerges here in a very personal way, in a letter about him by his fiancée, Harriet Lewin, to her sister. It is an atypical letter among the Lewin Papers (MS811), an archive which focuses on Harriet’s nephew Thomas Herbert Lewin (1839-1916), an administrator in India.

Grote’s courtship and marriage to Harriet were problematical. The relationship began with a misunderstanding when a rival led Grote to believe that Harriet was already engaged to somebody else (see here), and continued under a cloud of parental disapproval which meant that sole contact was by correspondence. The letter is dated 25 August 1818, shortly after her engagement, and indicates something of the relief of the written word and the general lack of sympathy towards the young bride to be: “You know him, and have the capability of appreciating those qualities which ‘pass outward shew’, whilst the rest of my family judge entirely of him by exterior qualities”.

Ultimately the couple married clandestinely in 1820. They were very happy, despite Harriet’s poor health and the disappointment of remaining childless. Although Harriet was unable to ensure Grote’s posterity through offspring, she compensated by becoming his first biographer (1873).

A Virginian visit: crossing an ocean and several centuries

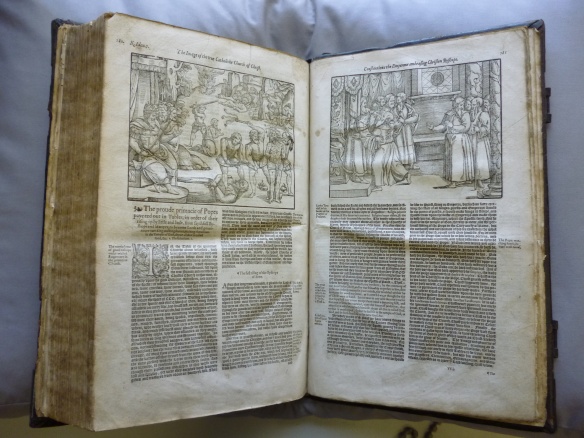

On Thursday 26 September a group of seven students from the James Madison University in Virginia came with their teacher, book historian Mark Rankin, to view sixteenth- and early-seventeenth century books in the Senate House Library collections. The topic of the session was martyrology, and students pored enthusiastically over illustrations in two sixteenth-century editions of Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. These included a set of twelve half-page woodcuts and a large folded leaf of plates depicting the gruesome tortures suffered by some of the martyrs, from the extraction of finger nails to the inevitable burning alive. The overtly Protestant nature of the illustrations was pointed out: for example, how in one instance a man’s dog was burned with him because he had held it up in mockery of the mass, and how the Pope was shown in a house window – with a woman. (Also displayed was John Bale’s Actes or Vnchaste Examples of the Englyshe Votaryes, condemning the allegedly intemperate activities of monks.)

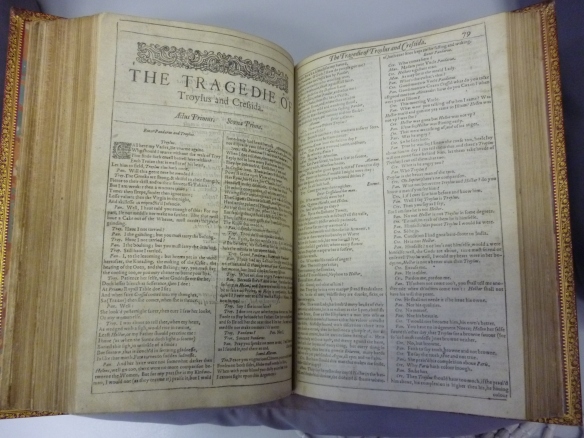

Beyond martyrology, students saw examples of early printing. A copy of the encyclopaedia De Proprietatibus Rerum from approximately 1471 served multiple purposes: to show a book printed by William Caxton in Cologne before he commenced printing in England; to demonstrate the hybrid nature of early printing, with initials added in manuscript in red and blue; and to point out different perceptions of learning over time, with medicine here being viewed as belonging to the humanities. Shakespearean sources also featured, with two editions of Holinshed’s Chronicles. Attention focused on Macbeth, for which Holinshed provides the major source, and vocabulary was compared between Holinshed and the First Folio: were the three witches weird, as described by Holinshed, or were they wayward, the adjective used in the First Folio and then abandoned? The highlight for the students was indubitably the sight of Shakespeare’s First Folio. Troilus and Cressida received special mention, the reason being that the text is in the volume but not listed in the table of contents.

Early printed books can be exciting and mysterious. The students experienced this; and watching their journey of discovery, the message came across clearly to the facilitating staff too.

Books Beyond their Texts – Material Culture Workshop

On Monday, 23 September eighteen early career researchers and doctoral students from several colleges of the University of London and from six other Universities came together at Senate House Library for a day’s workshop on material culture. The morning focused on book production in the hand-press period: how books differed from each other even when they left the printer’s shop, owing to such matters as printing variants and differences in the hand-made paper, and how further differences accrued through manuscript additions to texts, ownership, and bindings. All demonstrate the value of the artefact to teach us the book’s history in a way that full-text databases cannot do.

Such a workshop can take place only with the help of books. The morning’s session ended with a display of books to show various features: a cheap sixteenth-century volume copiously marked and annotated by an early reader; fifteenth-century tomes with spaces left on the printed pages for initials to be added in manuscript (neglected in one instance and inserted sumptuously in the other); an early, substantial book from 1508 with hand-coloured illustrations; a rare ephemeral early-seventeenth-century school textbook as an example of the low survival rate of such items; books whose producers had attempted to hide their origins; and the 1611 King James Bible, to show how the antiquated black letter typeface made a statement about the work’s authority.

After lunch, students paired off to examine more books. Senate House Library is fortunate to hold eleven copies of Francis Bacon’s Historie of the Raigne of King Henry the Seuenth (1622). This publication is notoriously complicated, with printed sheets of two identified issues (STC 1159-60) mixed together. Participants checked the noted variants in their copies to establish that hardly any of the nine were quite the same, owing to differences of spelling (for example, “raigne”/”reigne”; “souldiers”/”souldiours”) and the number of errata in each copy. Differences multiplied as we saw how some copies were bound with other works; how bindings varied from contemporary to twentieth-century and from cheap to decorative; and how owners had added to the individuality of their copies with inscriptions and bookplates. Most distinctively, one twentieth-century Baconian, Henry Seymour, had written a code in his copy to try to show how it indicated Bacon’s authorship of Shakespeare. We finished by looking at the meaning books gain by being part of specific collections: several of the copies had belonged to Sir Edwin Durning-Lawrence (1837-1914), who believed Francis Bacon to be one of England’s greatest men, who collected his works comprehensively, and for whom comprehensiveness extended beyond possessing different translations and editions to owning variants within editions.

In the final workshop students again paired off to ascertain what they could from seventeenth- and eighteenth-century books from different countries, in different languages and in different formats. They looked at cheapness and expense; at convenience of transportation; at probable use; and at possible laziness – were all the full-page illustrations in a book about machines meant to be grouped together at the front, or had a binder merely not bothered to intersperse them intelligently within the text, or received no instructions for doing so?

The day was the second of four workshops devoted to material culture. The workshops are facilitated by the Institute of Historical Research and enabled by AHRC funding. It was a pleasure for Senate House Library to take part.

Beautiful Things: Blake’s Illustrations of Dante

Continuing our irregular series of ‘Beautiful Things’ from the Library’s collections, we return to the Sterling Library and one of its many irreplaceable treasures: a set of engravings of seven of William Blake’s illustrations of the Divine Comedy.

Towards the end of his life, Blake was commissioned by his patron, engraver and painter John Linnell, to produce a set of illustrations of Dante’s masterpiece. Blake began 102 watercolour designs which reached various stages of completion before his death (and can be viewed on The William Blake Archive). Of these, seven, depicting scenes from the Inferno, were selected to be engraved by Blake. The Sterling Library set is one of five proofs produced for Linnell in 1826, and was in the possession of his family until 1918. As with the watercolours, the plates were unfinished at the time of Blake’s death, but the pure line engravings (a change from Blake’s technique of combining etching and engraving) produced are powerful and elegant, while the prints themselves are of exceptional quality and freshness, having been carefully stored by the Linnells.

Linnell did not produce prints of the plates for sale until 1838, and although Blake’s illustrations have since been used in many editions of the text, they were not widely known or used in the nineteenth century. Selections from the watercolours and prints were reproduced in the Savoy in 1896, accompanied by essays by W.B Yeats and in his 1899 bibliography of illustration of the Divine Comedy, Ludwig Volkmann wrote of the illustrations ‘although to-day almost forgotten and never mentioned in any treatise on the pictures to Dante, are to be ranked among the most interesting artistic works suggested by the Comedy’ (Iconografia Dantesca, 1899, p. 134). This is clearly demonstrated by the engravings: the scenes depicted are familiar from Dante’s text, but the interpretation is unique to Blake. The depiction of Dante and Virgil exemplify Blake’s vision: he does not follow the usual conventions of Dante illustration of attempting to reproduce a likeness of Dante or depicting Virgil as the typical classical poet, as Yeats writes ‘he intended to draw, in the present case, the soul rather than the body of Dante and read “The Divine Comedy” as a vision seen not in the body but out of the body.” (‘Blakes illustrations to the Divine Comedy’ The Savoy, 1896, 4, pp. 38-41).

Today, Blake’s illustrations are widely reproduced and easily recognisable but this particular set of prints are to be valued for their quality and provenance and, although unfinished are a beautiful example of Blake’s skill as an illustrator and engraver.

Quotes are taken from Dorothy L. Sayer’s translation of the Divine Comedy

Inferno, Canto V: the circle of the lustful and the encounter with Francesca da Rimini.

Like as the starlings wheel in the wintry season

In wide and clustering flocks wing-borne, wind-borne

Even so they go, the souls who did this treason,

…

While the one spirit thus spoke, the other’s crying,

Wailed on me with a sound so lamentable,

I swooned for like as I were dying,

And , as a dead man falling, down I fell.

(lines 40-42, 139-142)

Inferno, canto XXV: circle viii, bolgia vii: thieves: Cianfa, in the form of a reptile attacks and merges with Agnello.

Clasping his middle with its middle paws ,

Along his arms it made its fore-paws reach,

And clenched its teeth tightly in both jaws;

(lines 52-54)

Senate House Library treasures volume: featuring an unfortunate earl

MS 287 is a copy of a tract by Robert Devereux, second earl of Essex (1565-1601), addressed anonymously to Anthony Bacon (a device that enabled Essex to deny authorship), entitled:

‘To Maister Anthonie Bacon. An Apologie of the Earle of Essex, against those which falsely and maliciously taxe him to be the only hinderer of the Peace, and quiet of his Countrey.’

The text differs slightly from that of the first printed edition of 1600 (STC 6787.7) which also included a letter from Essex’s sister, Lady Rich, ‘to her maiestie, in the behalf of the earle of Essex’.

About the tract’s publication, Rowland Whyte wrote on 10 May 1600 to Sir Robert Sydney that ‘Lord Essex continues where he did: he plays now and then at tennis. An Apology written by him about the peace, is, as I hear, printed; on which he is much troubled, and has sent to the Stationers [Company] to suppress them, for it is done without his knowledge’. On 13 May Whyte reported that ‘The Queen is offended that this Apology of peace is printed, for of 200 copies only 8 is heard of. It is said that my Lady Riches letter to her Majesty is also printed, which is an exceeding wrong done to the Earle of Essex’.

Royal displeasure was something that Essex could ill afford. In 1598 his high standing as Queen Elizabeth’s favourite had been strained by a series of disastrous enterprises. He recovered sufficiently to be appointed Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1599, charged with destroying the rebellion led by the Earl of Tyrone. Having instead concluded a peace treaty with Tyrone, Essex was imprisoned and charged with treason on 20 March 1600. He survived that crisis, but led an abortive rebellion to unseat the queen, and he was executed on 25 February 1601.

The manuscript has a distinguished provenance. It first belonged to Sir Julius Caesar (1558-1636), a distinguished lawyer and judge who became chancellor of the Exchequer in 1606, and was master of the Rolls from 1614 to 1636. The antiquarian Horace Walpole (1719-1797) and the antiquarian and book collector Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792-1872) were subsequent owners.

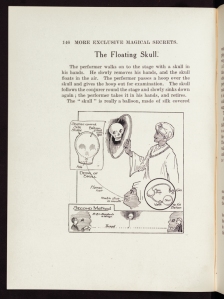

Senate House Library treasures volume: Featuring magic

The psychical researcher and writer Harry Price (1881-1948) was quick to describe rare and unusual books in his library. As far as I know, he did not write about Will Goldston’s More Exclusive Magical Secrets (1921). For Price it would have lacked the glamour of the pre-twentieth-century books in his library: it was less scarce for one thing (the limited de luxe edition comprised 750 numbered copies, of which 250 were destined for British readership), besides which the writer was Harry Price’s friend. But his copy is worth celebrating. It is the first in the numbered series, and it contains a handwritten dedication on its title page: ‘Congratulations to friend Harry Price. You possess the 1st copy many hours before other subscribers receive their copies. Best wishes. Sincerely yours Will Goldston November 1921.’

More Exclusive Magical Secrets is the second in a series of three which began with Exclusive Magical Secrets (1912) and ended with Further Exclusive Magical Secrets (1927); all three were issued with a substantial brass lock to emphasise secrecy. The volume contains sections on ‘pocket tricks’ (disappearing coins and cigarettes, ‘the cut string restored’, etc.) ‘small apparatus tricks’ ‘platform and stage tricks’, ‘Chinese tricks’, and ‘automata and ventriloquial’ devices. Perhaps the most interesting section in relation to Harry Price’s interests is that dealing with ‘anti-spiritualistic tricks’. The tricks explained include ‘The Talking Skull’, ‘A New Spirit Slate’ ‘A Spirit Rapping Table’, as well as ‘The Crystal Evulgograph’ (‘writing-revealer’), invented by Harry Price himself (pp. 108-12) and contributing, perhaps, to Goldston’s inscription.

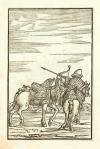

Senate House Library treasures volume: featuring exotic travel

In 1549 in Vienna the renowned Austrian diplomat and scholar Freiherr Sigmund von Herberstein (1486-1566) published his Rerum moscoviticarum commentarii, the detailed account of two embassies he had undertaken to the Muscovy of Grand-Duke Vasilii III, in 1517-18 and in 1526-7 for Archduke Ferdinand I.

Priding himself on his knowledge of languages that included Russian and on a method of gathering information based on personal observation, probing conversations, and careful scrutiny of documentary sources, Herberstein offered sixteenth-century Europe a wide-ranging survey and commentary on what in later books would be called ‘the present and past state’ of Muscovy or Russia. He provided information on the geography, the governance, the people, their customs and their religion with a degree of persuasive accuracy that brought his book best-seller status and made it widely influential in shaping subsequent views of the country. Herberstein’s work was not only one of the earliest examples of travel writing on Muscovy but became the virtually uncontested source of information, acknowledged and unacknowledged, for almost all subsequent writers into the seventeenth century.

This is one of three copies of the text from the collection of the historian Matthew Smith Anderson (1923-2006), who both wrote and collected about western perceptions of Russia to the period of the Russian Revolution. The other two are a second copy of this early translation into Italian, without the map at the end, and a Latin folio of 1551. This copy has a particular significance within the collection to which it belongs as the final item Anderson purchased for it.

![[S.L.] IV [Blake - 1826] fol-5105](https://senatehouselibraryhistoriccollections.files.wordpress.com/2013/09/s-l-iv-blake-1826-fol-5105.jpg?w=584&h=414)

![[S.L.] IV [Blake - 1826] fol-5100](https://senatehouselibraryhistoriccollections.files.wordpress.com/2013/09/s-l-iv-blake-1826-fol-5100.jpg?w=584&h=414)